|

|

October 2001

L'Alliance Francaise de Kandy, Sri Lanka invites you to a festival of books and to an encounter with Victor Segalen (1878-1919), André Malraux (1901-1976) and Albert Camus (1913-1960).

|

Alliance Française de Kandy,

412, Peradeniya Rd,

Kandy, Sri Lanka.

Tel : 00 94 8 22 44 32

e-mail : allikdy@sltnet.lk |

|

|

17th October

16h00

18th October

18h00

19h00

18h30

20th October

10h00

15h00

23th October

18h30

|

Poster drawing festival by the students under the theme of reading.

Opening of the new library : Bibliothèque Victor Segalen.

Albert Camus - "The Outsider" - adapted for stage monologue by Marc Amerasinghe.

Opening of the exhibition - "André Malraux speaks of Sri Lanka" - evocation in commemoration of his 100th birth anniversary. Exhibition continues to the 26th Otober between 10.00 a.m. and 6.00 p.m.

"A Fun Fair of Books" - Exhibition and sale of book in partnership with Gunasena & Co.,

Exhibition and sale continues till the 23 October between 10.00 a.m. and 6.00 p.m.

Round table discussion with Dr. Piyasiri Wijenaike (author and translator).

Lecture by Gérard Robuchon

(French Lecturer, Université of Kelaniya, Sri Lanka) - "Victor Segalen : One of the first French writers discovering Buddhism in Ceylon."

|

www.lire-en-fete.culture.fr

Seeing the world and having seen it, telling one's vision.

I saw it in its diversity.

This diversity, I wanted to give back its taste.

23rd of May, 1919...

The body of a still young man is found at the foot of a tree in a forest in Britanny - copy of Shakespear's Hamlet at his side, On his leg, a deep wound covered with a rough bandage.

" I do not have any sickness that can be detected

But however, it seems to me that I am seriously sick

I do not weigh myself anymore, medicines are of no importance to me

I simply realise that life is getting away from me"

And in this way ends the life of a great French poet whose writings take the many different colours of the cultures he met during his career as a navy Doctor.

Writer, traveller, ethnographer, his talent lies in his efforts to put face to face the forces of the imaginary and the real, of literature and action.

This "journey to the land of reality" is undertaken in order to give some substance to the words of the poet, in order to provide them with all their weight of reality.

Born in Brittany in 1878, he obtains his Doctorate in Medicine in 1902 , the subject of his research being " the neuroses in contemporary literature".

Then starts his geographical and mental journeys: the first of these many great travels taking him to Polynesia with the idea of reviving the Maorian culture - following the model of Gauguin and to the discovery of the Chinese continent.

He sees the end of a race, the end of a culture, the Maorian culture - later, in China, it will be the agony of a myth, the myth of the Emperor, son of the sky.

1903, he arrives in Tahiti where he discovers the remains of the Maorian culture ruined by European presence. On a brief stopover in the Marquises islands, his attention falls on the last sketches done by Gauguin, dead three months ago.

Paul Gaugin, a meeting that never happened, but a decisive one.

|

Resulting from his stay in the Polynesia, he produces a book 'Les Immémoriaux" (A Lapse of Memory), published in 1907.

The tragedy of a race which has lost the meaning of the 'sacred'. A cry of alarm then one of farewell to which the answer will be soon the silence.

The liberation of a man whose identity was revealed by these islands.

The passionate nostalgia of a forgotten people.

|

|

|

1908 He becomes interested in China and by 1910 he wishes to serve as a translator his wife and son. He publishes the first edition of Stèles in Beijing in 1912.

A somewhat 'strange' personality, who has secured his place in the royal line-up of visionary poets for whom Poetry is a means of going beyond the human condition.

This poet, this doctor fascinated by the complexity of unconscious, this archaeologue, ethnologue, pioneer of sinology was, by spirit and by nature a researcher, an explorer.

|

During an archaeological expedition in China, his work is interrupted by the war and so, he returns to France, works in the war front for some time and returns to China to recruit volunteers. He continues his research in archaeology.

At the end of the year 1917, sick, he leaves the East forever.

Orientalist, in search of exoticism, though not a 'spoilt exoticism' but one which translates for him the idea of 'difference', everything that refers to 'the other'. He invents the term "exote" to refer to 'the ideal traveller, always a stranger and always xénophile".

The sensation of exotism, which is none other than the notion of being different, the perception of Diversity, the understanding that something is not yourself, and the power of exoticism, which is none other than the ability to recognise the other.

For him, exotism does not mean melting in the Other, rejecting one's self, making the foreign culture one's own.

Although I felt strongly about China, it did not lead me to becoming Chinese. Deep feelings about the dawn of Vedas did not make me regret that I was not born as a shepherd three thousand years ago.

Only those who possess a strong individuality are able to sense the difference.

Almost all his works, written between 1909 and 1913 has, as its hidden theme, his conception of exoticism, which he considers as an "aesthetic of difference". And so, he asks from Tahiti, China or Tibet only to show him their true faces and to leave him to discover their deep reality through which he will nourish his vision.

That is what he asks from Ceylon as well on a day in November 1904 when a sudden stopover leads him to discover Colombo and Kandy and this brief encounter draws the first sketches of his book "Siddhartha".

Native Bullock Carts, Ceylon. (c) Plâté & Co.,

Native Bullock Carts, Ceylon. (c) Plâté & Co.,

|

Colombo, Thursday, 7th November 1904

We get closer. The pirogues with fluttering huge red sails

The first steps on this land are full of exoticism...

The picturesque bursts as always with the different means of transport,

Large chariots with immense wheels drawn by bulls...

|

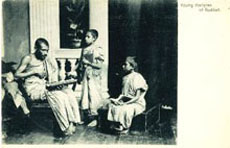

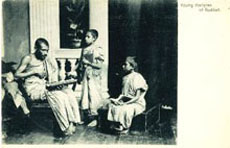

Young disciples of Buddha. (c) Plâté & Co.,

Young disciples of Buddha. (c) Plâté & Co.,

|

Kandy, Friday, 8th November 1904

I walk round the lake. My footsteps take me towards the monk. He is young, bright shining eyes... and sometimes in the pose of a monk, sitting against the light on the bed, it seems to me that everything is flying away, that hut whitened by chalk, low and dull, flies away in fragments, that a light radiates...

Thursday, 22nd December 1904

Day of the full moon - Poya. Almost my last night in Ceylon, this night - excellent, pure, lactescent and fragrant... |

This journey to the Far-East, the answer is a dive into his internal universe of which is reflected in his writings...

As always one makes a long journey which is none other than a journey into ones own self.

It is through the path of diversity that one reaches the centre, that means into the self.

A multiple being, a meeting point of languages, polyphonic individual, an artist, fond of beauty

An entirely aesthetic belief, an exclusive research of beauty, a permanent desire to reach, the beauty everywhere, an to realise out of them a reflection in his thinking, in his action, above all in his works.

At a time where everything has become so uniform

thus ruining the priceless diversity of the Other

He helps us to still believe in

the myth of the metamorphose through travels

Existence finds its splendor in Difference and in Diversity

The Difference decreases. There lies the immense danger...

So says in 1917 this great French poet

Victor Segalen |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Native Bullock Carts, Ceylon. (c) Plâté & Co.,

Native Bullock Carts, Ceylon. (c) Plâté & Co.,

Young disciples of Buddha. (c) Plâté & Co.,

Young disciples of Buddha. (c) Plâté & Co.,